17 KiB

Memory Aliasing and noalias

Memory aliasing is an important concept that can lead to significant optimizations for a compiler that is aware about how data is being used by the code.

The problem

Let's take a simple example of a job copying data from an input array to an output array:

[BurstCompile]

private struct CopyJob : IJob

{

[ReadOnly]

public NativeArray<float> Input;

[WriteOnly]

public NativeArray<float> Output;

public void Execute()

{

for (int i = 0; i < Input.Length; i++)

{

Output[i] = Input[i];

}

}

}

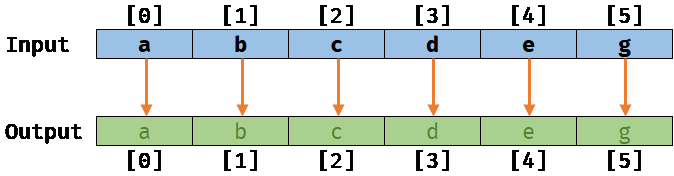

No memory aliasing:

If the two arrays Input and Output are not slightly overlapping, meaning that their respective memory location are not aliasing, we will get the following result after running this job on a sample input/output:

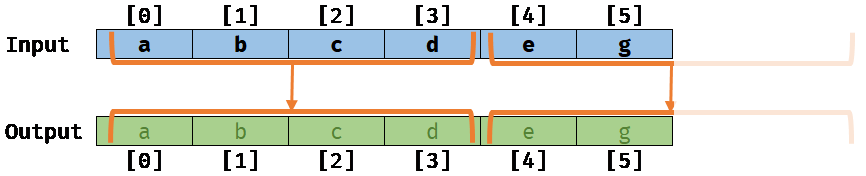

No memory aliasing with the auto-vectorizer:

Now, if the compiler is noalias aware, it will be able to optimize the previous scalar loop (working at a scalar level) by what is called vectorizing: The compiler will rewrite the loop on your behalf to process elements by a small batch (working at a vector level, 4 by 4 elements for example) like this:

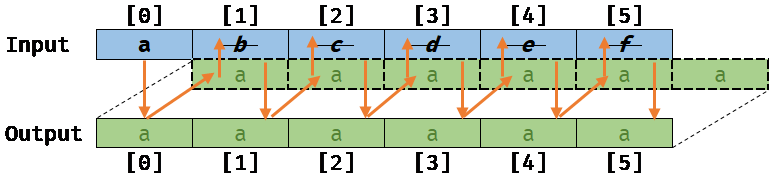

Memory aliasing:

Next, if for some reasons (that is not directly easy to introduce with the JobSystem today), the Output array is actually overlapping the Input array by one element off (e.g Output[0] actually points to Input[1]), meaning that memory is aliasing, we will get the following result when running the CopyJob (assuming that the auto-vectorizer is not running):

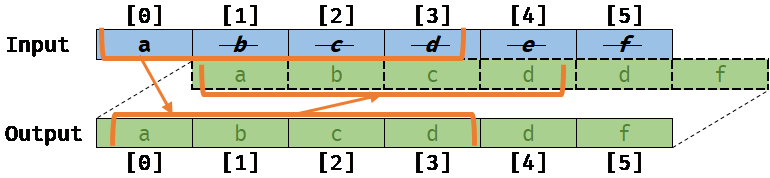

Memory aliasing with invalid vectorized code:

Worse, if the compiler was not aware of this memory aliasing, it would still try to auto-vectorize the loop, and we would get the following result, which is different from the previous scalar version:

The result of this code would be invalid and could lead to very serious bugs if they are not identified by the compiler.

Example of Generated Code

Let's take the example of the x64 assembly targeted at AVX2 for the loop in the CopyJob above:

.LBB0_4:

vmovups ymm0, ymmword ptr [rcx - 96]

vmovups ymm1, ymmword ptr [rcx - 64]

vmovups ymm2, ymmword ptr [rcx - 32]

vmovups ymm3, ymmword ptr [rcx]

vmovups ymmword ptr [rdx - 96], ymm0

vmovups ymmword ptr [rdx - 64], ymm1

vmovups ymmword ptr [rdx - 32], ymm2

vmovups ymmword ptr [rdx], ymm3

sub rdx, -128

sub rcx, -128

add rsi, -32

jne .LBB0_4

test r10d, r10d

je .LBB0_8

As can be seen above, the instruction vmovups is moving 8 floats here, so a single auto-vectorized loop is now moving 4 x 8 = 32 floats copied per loop iteration instead of just one!

If we compile the same loop but artificially disable Burst's knowledge of aliasing, we get the following code:

.LBB0_2:

mov r8, qword ptr [rcx]

mov rdx, qword ptr [rcx + 16]

cdqe

mov edx, dword ptr [rdx + 4*rax]

mov dword ptr [r8 + 4*rax], edx

inc eax

cmp eax, dword ptr [rcx + 8]

jl .LBB0_2

Which is entirely scalar and will run roughly 32 times slower than the highly optimized, vectorized variant that our alias analysis can produce.

Burst and the JobSystem

Unity's job-system infrastructure imposes certain rules on what can alias within a job struct:

- Structs attributed with

[NativeContainer](for example -NativeArrayandNativeSlice) that are members of a job struct do not alias. - But job struct members with the

[NativeDisableContainerSafetyRestriction]attribute can alias with other members (because you, as the user, have explicitly opted in to this aliasing). - Pointers to structs attributed with

[NativeContainer]cannot appear within other structs attributed with[NativeContainer]. For example, you cannot have aNativeArray<NativeSlice<T>>. This kind of spaghetti code is awful for optimizing compilers to understand.

Let us now look at an example job:

[BurstCompile]

private struct MyJob : IJob

{

public NativeArray<float> a;

public NativeArray<float> b;

public NativeSlice<int> c;

[NativeDisableContainerSafetyRestriction]

public NativeArray<byte> d;

public void Execute() { ... }

}

In the above example:

a,b, andcdo not alias with each other.- But

dcan alias witha,b, orc.

Those of you used to C/C++'s Type Based Alias Analysis (TBAA) might think 'But d has a different type from a, b, or c, so it should not alias!' - pointers in C# do not have any assumption that pointing to a different type results in no aliasing, though. So d must be assumed to alias with a, b, or c.

The NoAlias Attribute

Burst has a [NoAlias] attribute that can be used to give the compiler additional information on the aliasing of pointers and structs. There are four uses of this attribute:

- On a function parameter it signifies that the parameter does not alias with any other parameter to the function.

- On a struct field it signifies that the field does not alias with any other field of the struct.

- On a struct itself it signifies that the address of the struct cannot appear within the struct itself.

- On a function return value it signifies that the returned pointer does not alias with any other pointer returned from the same function.

These attributes do not need to be used when dealing with [NativeContainer] attributed structs, or with fields in job structs - the Burst compiler is smart enough to infer the no-alias information about these without manual intervention from you, our users. This leads onto a general rule of thumb - the use of the [NoAlias] attribute is generally not required for user code, and we advise against its use. The attribute is exposed primarily for those constructing complex data structures where the aliasing cannot be inferred by the compiler. Any use of [NoAlias] attribute on a pointer that could alias with another could result in undefined behaviour and make it hard to track down bugs.

NoAlias Function Parameter

Let's take a look at the following classic aliasing example:

int Foo(ref int a, ref int b)

{

b = 13;

a = 42;

return b;

}

For this the compiler produces the following assembly:

mov dword ptr [rdx], 13

mov dword ptr [rcx], 42

mov eax, dword ptr [rdx]

ret

As can be seen it:

- Stores 13 into

b. - Stores 42 into

a. - Reloads the value from

bto return it.

It has to reload b because the compiler does not know whether a and b are backed by the same memory or not.

Let's now add a [NoAlias] attribute and see what we get:

int Foo([NoAlias] ref int a, ref int b)

{

b = 13;

a = 42;

return b;

}

Which turns into:

mov dword ptr [rdx], 13

mov dword ptr [rcx], 42

mov eax, 13

ret

Notice that the load from b has been replaced with moving the constant 13 into the return register.

NoAlias Struct Field

Let's take the same example from above but apply it to a struct instead:

struct Bar

{

public NativeArray<int> a;

public NativeArray<float> b;

}

int Foo(ref Bar bar)

{

bar.b[0] = 42.0f;

bar.a[0] = 13;

return (int)bar.b[0];

}

The above produces the following assembly:

mov rax, qword ptr [rcx + 16]

mov dword ptr [rax], 1109917696

mov rcx, qword ptr [rcx]

mov dword ptr [rcx], 13

cvttss2si eax, dword ptr [rax]

ret

As can be seen it:

- Loads the address of the data in

bintorax. - Stores 42 into it (1109917696 is 0x42280000 which is 42.0f).

- Loads the address of the data in

aintorcx. - Stores 13 into it.

- Reloads the data in

band converts it to an integer for returning.

Let's assume that you, as the user, know that the two NativeArray's are not backed by the same memory. Therefore you could do this:

struct Bar

{

[NoAlias]

public NativeArray<int> a;

[NoAlias]

public NativeArray<float> b;

}

int Foo(ref Bar bar)

{

bar.b[0] = 42.0f;

bar.a[0] = 13;

return (int)bar.b[0];

}

By attributing both a and b with [NoAlias] we have told the compiler that they definitely do not alias with each other within the struct, which produces the following assembly:

mov rax, qword ptr [rcx + 16]

mov dword ptr [rax], 1109917696

mov rax, qword ptr [rcx]

mov dword ptr [rax], 13

mov eax, 42

ret

Notice that the compiler can now just return the integer constant 42!

NoAlias Struct

Nearly all structs you will create as a user will be able to have the assumption that the pointer to the struct does not appear within the struct itself. Let's take a look at a classic example where this is not true:

unsafe struct CircularList

{

public CircularList* next;

public CircularList()

{

// The 'empty' list just points to itself.

next = this;

}

}

Lists are one of the few structures where it is normal to have the pointer to the struct accessible from somewhere within the struct itself.

Now onto a more concrete example of where [NoAlias] on a struct can help:

unsafe struct Bar

{

public int i;

public void* p;

}

float Foo(ref Bar bar)

{

*(int*)bar.p = 42;

return ((float*)bar.p)[bar.i];

}

Which produces the following assembly:

mov rax, qword ptr [rcx + 8]

mov dword ptr [rax], 42

mov rax, qword ptr [rcx + 8]

mov ecx, dword ptr [rcx]

movss xmm0, dword ptr [rax + 4*rcx]

ret

As can be seen it:

- Loads

pintorax. - Stores 42 into

p. - Loads

pintoraxagain. - Loads

iintoecx. - Returns the index into

pbyi.

Notice that it loaded p twice - why? The reason is that the compiler does not know whether p points to the address of the struct bar itself - so once it has stored 42 into p, it has to reload the address of p from bar, just in case. A wasted load!

Let's add [NoAlias] now:

[NoAlias]

unsafe struct Bar

{

public int i;

public void* p;

}

float Foo(ref Bar bar)

{

*(int*)bar.p = 42;

return ((float*)bar.p)[bar.i];

}

Which produces the following assembly:

mov rax, qword ptr [rcx + 8]

mov dword ptr [rax], 42

mov ecx, dword ptr [rcx]

movss xmm0, dword ptr [rax + 4*rcx]

ret

Notice that it only loaded the address of p once, because we've told the compiler that p cannot be the pointer to bar!

NoAlias Function Return

Some functions can only return a unique pointer. For instance, malloc will only ever give you a unique pointer. For these cases [return:NoAlias] can provide some useful information to the compiler.

Let's take an example using a bump allocator backed with a stack allocation:

// Only ever returns a unique address into the stackalloc'ed memory.

// We've made this no-inline as the compiler will always try and inline

// small functions like these, which would defeat the purpose of this

// example!

[MethodImpl(MethodImplOptions.NoInlining)]

unsafe int* BumpAlloc(int* alloca)

{

int location = alloca[0]++;

return alloca + location;

}

unsafe int Func()

{

int* alloca = stackalloc int[128];

// Store our size at the start of the alloca.

alloca[0] = 1;

int* ptr1 = BumpAlloc(alloca);

int* ptr2 = BumpAlloc(alloca);

*ptr1 = 42;

*ptr2 = 13;

return *ptr1;

}

Which produces the following assembly:

push rsi

push rdi

push rbx

sub rsp, 544

lea rcx, [rsp + 36]

movabs rax, offset memset

mov r8d, 508

xor edx, edx

call rax

mov dword ptr [rsp + 32], 1

movabs rbx, offset "BumpAlloc(int* alloca)"

lea rsi, [rsp + 32]

mov rcx, rsi

call rbx

mov rdi, rax

mov rcx, rsi

call rbx

mov dword ptr [rdi], 42

mov dword ptr [rax], 13

mov eax, dword ptr [rdi]

add rsp, 544

pop rbx

pop rdi

pop rsi

ret

It's quite a lot of assembly, but the key bit is that it:

- Has

ptr1inrdi. - Has

ptr2inrax. - Stores 42 into

ptr1. - Stores 13 into

ptr2. - Loads

ptr1again to return it.

Let's now add our [return: NoAlias] attribute:

[MethodImpl(MethodImplOptions.NoInlining)]

[return: NoAlias]

unsafe int* BumpAlloc(int* alloca)

{

int location = alloca[0]++;

return alloca + location;

}

unsafe int Func()

{

int* alloca = stackalloc int[128];

// Store our size at the start of the alloca.

alloca[0] = 1;

int* ptr1 = BumpAlloc(alloca);

int* ptr2 = BumpAlloc(alloca);

*ptr1 = 42;

*ptr2 = 13;

return *ptr1;

}

Which produces:

push rsi

push rdi

push rbx

sub rsp, 544

lea rcx, [rsp + 36]

movabs rax, offset memset

mov r8d, 508

xor edx, edx

call rax

mov dword ptr [rsp + 32], 1

movabs rbx, offset "BumpAlloc(int* alloca)"

lea rsi, [rsp + 32]

mov rcx, rsi

call rbx

mov rdi, rax

mov rcx, rsi

call rbx

mov dword ptr [rdi], 42

mov dword ptr [rax], 13

mov eax, 42

add rsp, 544

pop rbx

pop rdi

pop rsi

ret

And notice that the compiler doesn't reload ptr2 but simply moves 42 into the return register.

[return: NoAlias] should only ever be used on functions that are 100% guaranteed to produce a unique pointer, like with the bump-allocating example above, or with things like malloc. It is also important to note that the compiler aggressively inlines functions for performance considerations, and so small functions like the above will likely be inlined into their parents and produce the same result without the attribute (which is why we had to force no-inlining on the called function).

Function Cloning for Better Aliasing Deduction

For function calls where Burst knows about the aliasing between parameters to the function, Burst can infer the aliasing and propagate this onto the called function to allow for greater optimization opportunities. Let's look at an example:

[MethodImpl(MethodImplOptions.NoInlining)]

int Bar(ref int a, ref int b)

{

a = 42;

b = 13;

return a;

}

int Foo()

{

var a = 53;

var b = -2;

return Bar(ref a, ref b);

}

Previously the code for Bar would be:

mov dword ptr [rcx], 42

mov dword ptr [rdx], 13

mov eax, dword ptr [rcx]

ret

This is because the compiler did not know the aliasing of a and b within the Bar function. This is in line with what other compiler technologies will do with this code snippet.

Burst is smarter than this though, and through a process of function cloning Burst will create a copy of Bar where the aliasing properties of a and b are known not to alias, and replace the original call to Bar with a call to the copy. This results in the following assembly:

mov dword ptr [rcx], 42

mov dword ptr [rdx], 13

mov eax, 42

ret

Which as we can see doesn't perform the second load from a.

Aliasing Checks

Since aliasing is so key to the compilers ability to optimize for performance, we've added some aliasing intrinsics:

Unity.Burst.CompilerServices.Aliasing.ExpectAliasedexpects that the two pointers do alias, and generates a compiler error if not.Unity.Burst.CompilerServices.Aliasing.ExpectNotAliasedexpects that the two pointers do not alias, and generates a compiler error if not.

An example:

using static Unity.Burst.CompilerServices.Aliasing;

[BurstCompile]

private struct CopyJob : IJob

{

[ReadOnly]

public NativeArray<float> Input;

[WriteOnly]

public NativeArray<float> Output;

public unsafe void Execute()

{

// NativeContainer attributed structs (like NativeArray) cannot alias with each other in a job struct!

ExpectNotAliased(Input.getUnsafePtr(), Output.getUnsafePtr());

// NativeContainer structs cannot appear in other NativeContainer structs.

ExpectNotAliased(in Input, in Output);

ExpectNotAliased(in Input, Input.getUnsafePtr());

ExpectNotAliased(in Input, Output.getUnsafePtr());

ExpectNotAliased(in Output, Input.getUnsafePtr());

ExpectNotAliased(in Output, Output.getUnsafePtr());

// But things definitely alias with themselves!

ExpectAliased(in Input, in Input);

ExpectAliased(Input.getUnsafePtr(), Input.getUnsafePtr());

ExpectAliased(in Output, in Output);

ExpectAliased(Output.getUnsafePtr(), Output.getUnsafePtr());

}

}

These checks will only be ran when optimizations are enabled - since proper aliasing deduction is intrinsically linked to the optimizers ability to see through functions via inlining.